Este es el denominado TRIÁNGULO DE LA ANGUSTIA Y TENSIÓN Los siguientes puntos energéticos son recomendados para calmar las tensiones mentales, relajar la muscu...latura de la zona alta de la espalda y liberar la angustia. Se trata de ejercer presiones con los dedos pulgares en cada par de puntos por 5 segundos para luego soltar (7 veces). Pídale a un familiar querido que le haga la terapia para un mejor efecto. VB 20 (Vesícula Biliar): En la base del hueso occipital. Los dos puntos están separados a unos 5 – 7 cm, coincidiendo con unas suaves cavidades palpables. - Alivia la depresión, dolores de cabeza, mareos, rigidez de cuello e irritabilidad. V 10 (Vejiga): Situado a un dedo por debajo de la base del hueso occipital y a dos dedos de distancia de la columna vertebral. - Actúa contra el estrés, agotamiento, insomnio, rigidez cervical y problemas oculares. TC 15 (Triple Calentador): Situado a medio camino entre la base del cuello y el extremo exterior de cada hombro, a 1 cm. por debajo de la línea alta del trapecio. – Excelente para aliviar la tensión nerviosa y la rigidez del cuello. Uno de los puntos que deben ser utilizados para tratar la fibromialgia V 38 (Vejiga): Situado a una distancia media entre la escápula y la columna vertebral, a la altura del corazón. - Equilibra trastornos emocionales como la ansiedad y depresión. CURSO A DISTANCIA "Medicina china -técnicas curativas" 4 didácticos manuales + 7 Libros digitales Informes: saczeta@hotmail.com medicinachinayogaperu@gmail.com Clases en Lima/Medicina China y Chikung telf (00511) 5780228 / Maestro César Ramírez T www.medicinachinayogaperu.com

domingo, 29 de diciembre de 2013

miércoles, 16 de octubre de 2013

jueves, 19 de septiembre de 2013

Nueva ubicación

Entre lluvias y obras ha estado algo errático todo esto, les dejamos esta ubicación actual donde iniciaremos a practicar.

Nueva ubicación mientras realizan obras en el parque de la calle Perseo.

Cruz del Sur esq. Canal Nacional

Martes y Viernes 6:00PM a 7:30PM

Domingo 8:30AM a 10:00AM+

Cruz del Sur esq. Canal Nacional

Martes y Viernes 6:00PM a 7:30PM

Domingo 8:30AM a 10:00AM+

domingo, 1 de septiembre de 2013

Qigong (chikung) para tristeza, melancolía, depresión.

Y creo yo además que para el temple cuerpo-mente-espíritu nada como media hora o más de abrazando el árbol o posición de caballo.

lunes, 1 de julio de 2013

Algunos métodos de TaiChi con lanza acorde a Chen Yanlin

TAIJI SPEAR METHODS ACCORDING TO CHEN YANLIN

-

太極扎桿

TAIJI THRUSTING POLE

TAIJI THRUSTING POLE

from

太極拳刀劍桿散手合編

Taiji Compiled: The Boxing, Saber, Sword, Pole, and Sparring

陳炎林

by Chen Yanlin

[published June, 1943]

太極拳刀劍桿散手合編

Taiji Compiled: The Boxing, Saber, Sword, Pole, and Sparring

陳炎林

by Chen Yanlin

[published June, 1943]

[translation by Paul Brennan, June, 2013]

-

太極扎桿

TAIJI THRUSTING POLE

TAIJI THRUSTING POLE

太極拳中之扎桿。亦稱沾黏桿。或曰十三勢桿。有十三字訣。開、合、崩、劈、點、扎、撥、撩、纏、帶、滑、截。為太極拳中重要功夫之一。其沾、黏、化、拿、引、發、諸勁。與徒手拳式相同。亦異常奧妙。練法分單人雙人兩種。功至深造時。桿卽如手。週身之勁。可直達桿頭。猶如水銀裝於管中。發可至首。收可至尾。斯種扎桿。練法用法。含有畫戟與大槍二種。近人若以之全為大槍者實誤。蓋其未明太極拳中扎桿之效用耳。楊氏扎桿。甚為著名。而楊露禪以之救火。誠奇聞也。(見卷一楊家小傳章內)其與人對桿時。無論拿人發人。皆如用手。人遇其桿。卽失自主。被擊出一如手發。往往不知其所以然。惜此種深奧功夫。今已失傳。考桿之練習方法。計分單人扎桿法。雙人平圓沾黏扎桿法。雙人立體圓形沾黏扎桿法。及雙人動步刺心、刺腿、刺肩、刺喉、四桿法等數種。茲分述於後。俾大好國術餘粹。得以保存。不致復失傳矣。

桿、一稱蠟桿。係籐類。產於河南山東等地。性韌而堅實。不易斷裂。昔時用作槍戟等之把柄。有青白兩種。以白而有皮者為佳。其中尤以長過丈三外。兩根成對。下部三尺各無節。三尺以上所有苞節。均陰陽相對者為最佳。稱之謂成品。如用藏得法。經年愈久。其色愈鮮紅。愛此者每作為古玩。惜此種成品桿子。今已罕見。

[While in Yang Chengfu’s 1931 manual such exercises are explicitly termed as “spear” (鎗) techniques, the word chosen in this book (桿) instead represents the unbladed spear-shaft, and as it is also a different character from the usual word for “staff” (棍), hence “pole”.]

Taiji Boxing’s “Thrusting Pole” is also known as “Stick & Adhere Pole”, or “Thirteen Dynamics Pole”, the thirteen being spreading, covering, flicking, chopping, tapping, thrusting, deflecting, raising, coiling, leading, sliding, and severing [although there are only twelve in this list]. As one of the major practices in Taiji Boxing, its energies of sticking, adhering, neutralizing, seizing, drawing in, and issuing are the same as with the bare-handed postures, it is likewise extremely subtle, and the practice method also divides into solo practice and partner practice.

Once your skill is deep, the pole is just like a hand, and the power of your whole body can reach straight to the tip, just as though mercury is being sent through a tube. When issuing, it reaches the tip, and when withdrawing, it reaches the tail.

These thrusting pole exercises, in practice and application, contain the methods of both the halberd and long spear. Those who nowadays treat it as though it is entirely based on the long spear are actually incorrect, indicating a lack of understanding as to the effectiveness of Taiji Boxing’s thrusting pole. The Yang family’s thrusting pole is very famous, Yang Luchan having even used it to help put out a fire, which is a truly remarkable thing to hear of. (See the chapter “Brief Yang Family Biographies” [included below in its entirety*].)

When you and an opponent face off with poles, whether seizing him or sending him away, it is all the same as using hands. Once an opponent connects with your pole, he immediately loses his initiative and has been hit just as if you were issuing with your hand, and he will typically not understand how it happened.

Alas, this depth of skill is already lost these days, but to consider the practice methods, there are several, which divide into the Solo Thrusting Pole Method, Two-Person Level-Circle Stick & Adhere Thrusting Pole Method, Two-Person Vertical-Circle Stick & Adhere Thrusting Pole Method, and the Two-Person Moving-Step Four Stabs to the Solar Plexus, Leg, Shoulder, and Throat. These are each described below so that connoisseurs of martial arts will be able to preserve them, preventing them from being lost all over again.

It is recommended that you use poles made of waxwood, related to rattan, which are produced in Henan or Shandong. They have a flexible hardness as well as a hardness of substance and are not easy to break.

They were long ago used as the handles for spears and halberds. They were of two types, a greenish black and a white, the white one being beautifully leathered. They were more than thirteen feet in length. As for the two ends, the lower three feet of it were unsectioned while the upper three feet were wrapped in sections. The optimum affect came from this balancing of opposites.

It was said of the finished product that it was as though the method had been obtained from scriptures. As years passed, it would redden in color. Adorers of such things often treat them as antiques, for unfortunately this method of fashioning poles is rarely seen nowadays.

桿、一稱蠟桿。係籐類。產於河南山東等地。性韌而堅實。不易斷裂。昔時用作槍戟等之把柄。有青白兩種。以白而有皮者為佳。其中尤以長過丈三外。兩根成對。下部三尺各無節。三尺以上所有苞節。均陰陽相對者為最佳。稱之謂成品。如用藏得法。經年愈久。其色愈鮮紅。愛此者每作為古玩。惜此種成品桿子。今已罕見。

[While in Yang Chengfu’s 1931 manual such exercises are explicitly termed as “spear” (鎗) techniques, the word chosen in this book (桿) instead represents the unbladed spear-shaft, and as it is also a different character from the usual word for “staff” (棍), hence “pole”.]

Taiji Boxing’s “Thrusting Pole” is also known as “Stick & Adhere Pole”, or “Thirteen Dynamics Pole”, the thirteen being spreading, covering, flicking, chopping, tapping, thrusting, deflecting, raising, coiling, leading, sliding, and severing [although there are only twelve in this list]. As one of the major practices in Taiji Boxing, its energies of sticking, adhering, neutralizing, seizing, drawing in, and issuing are the same as with the bare-handed postures, it is likewise extremely subtle, and the practice method also divides into solo practice and partner practice.

Once your skill is deep, the pole is just like a hand, and the power of your whole body can reach straight to the tip, just as though mercury is being sent through a tube. When issuing, it reaches the tip, and when withdrawing, it reaches the tail.

These thrusting pole exercises, in practice and application, contain the methods of both the halberd and long spear. Those who nowadays treat it as though it is entirely based on the long spear are actually incorrect, indicating a lack of understanding as to the effectiveness of Taiji Boxing’s thrusting pole. The Yang family’s thrusting pole is very famous, Yang Luchan having even used it to help put out a fire, which is a truly remarkable thing to hear of. (See the chapter “Brief Yang Family Biographies” [included below in its entirety*].)

When you and an opponent face off with poles, whether seizing him or sending him away, it is all the same as using hands. Once an opponent connects with your pole, he immediately loses his initiative and has been hit just as if you were issuing with your hand, and he will typically not understand how it happened.

Alas, this depth of skill is already lost these days, but to consider the practice methods, there are several, which divide into the Solo Thrusting Pole Method, Two-Person Level-Circle Stick & Adhere Thrusting Pole Method, Two-Person Vertical-Circle Stick & Adhere Thrusting Pole Method, and the Two-Person Moving-Step Four Stabs to the Solar Plexus, Leg, Shoulder, and Throat. These are each described below so that connoisseurs of martial arts will be able to preserve them, preventing them from being lost all over again.

It is recommended that you use poles made of waxwood, related to rattan, which are produced in Henan or Shandong. They have a flexible hardness as well as a hardness of substance and are not easy to break.

They were long ago used as the handles for spears and halberds. They were of two types, a greenish black and a white, the white one being beautifully leathered. They were more than thirteen feet in length. As for the two ends, the lower three feet of it were unsectioned while the upper three feet were wrapped in sections. The optimum affect came from this balancing of opposites.

It was said of the finished product that it was as though the method had been obtained from scriptures. As years passed, it would redden in color. Adorers of such things often treat them as antiques, for unfortunately this method of fashioning poles is rarely seen nowadays.

-

單人扎桿法

SOLO THRUSTING POLE METHOD

SOLO THRUSTING POLE METHOD

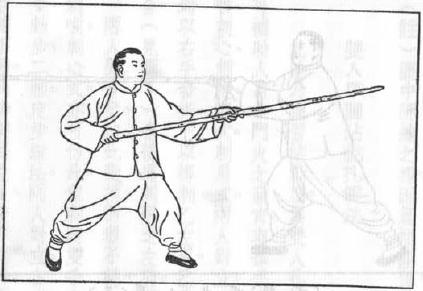

太極拳中之單人扎桿。甚為簡單。祗有開、(卽撥)合、(卽逼)發、(卽扎或刺)三字。練時左足向前。右手執桿尾部。左手執桿中央。兩足分開。成為如弓似馬之步法。週身鬆開。虛領頂勁。此為起勢。開式。右手下沉。左手移上。桿頭向上往左。全身重心移於右腿。眼神注視桿頭。(見圖1)

Taiji Boxing’s solo thrusting pole exercise is very simple. There are only three parts to it: spreading aside (or “deflecting”), covering (or “urging away”), and issuing (or “thrusting” / “stabbing”). When practicing with your left foot forward, your right hand holds the tail end of the pole and your left hand holds the middle. Your feet are spread apart, making a posture between a bow stance and a horse-riding stance. Your whole body is relaxed and your headtop is pressing up forcelessly. This is the starting posture.

Spreading:

Your right hand sinks down as your left hand shifts up, the pole tip going to the upper left. The weight of your body is shifted to your right leg. Your eyes are looking toward the pole tip. See drawing 1:

Taiji Boxing’s solo thrusting pole exercise is very simple. There are only three parts to it: spreading aside (or “deflecting”), covering (or “urging away”), and issuing (or “thrusting” / “stabbing”). When practicing with your left foot forward, your right hand holds the tail end of the pole and your left hand holds the middle. Your feet are spread apart, making a posture between a bow stance and a horse-riding stance. Your whole body is relaxed and your headtop is pressing up forcelessly. This is the starting posture.

Spreading:

Your right hand sinks down as your left hand shifts up, the pole tip going to the upper left. The weight of your body is shifted to your right leg. Your eyes are looking toward the pole tip. See drawing 1:

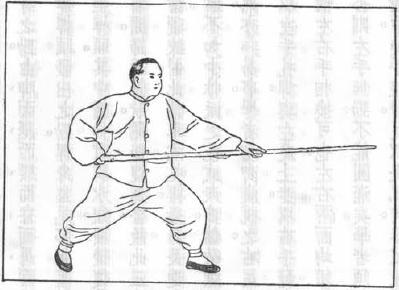

用法在敵人武器近身時。以此撥開。合式。雙手靠腰腿向下合。內含有一小圓圈。左手背翻上。右手掌向上。與開式適相反。重心分於兩腿。眼神仍注視桿頭。(見圖2)

Its application is to deflect aside an opponent’s weapon as it approaches your body.

Covering:

Both hands, dependent on your waist and thighs, cover downward. This action contains a small circle due to the turning upward of the back of your left hand and your right palm, the reverse of the spreading posture [in which the back of your left hand and your right palm turn downward]. The weight is evenly spread over both legs. Your eyes are looking toward the pole tip. See drawing 2:

Its application is to deflect aside an opponent’s weapon as it approaches your body.

Covering:

Both hands, dependent on your waist and thighs, cover downward. This action contains a small circle due to the turning upward of the back of your left hand and your right palm, the reverse of the spreading posture [in which the back of your left hand and your right palm turn downward]. The weight is evenly spread over both legs. Your eyes are looking toward the pole tip. See drawing 2:

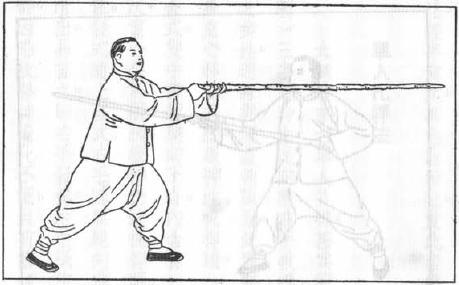

用法。在敵人武器近身時。以此逼住。發式。隨上合式。右手隨腰腿向前發桿。右手虎口向上。左手不動。桿在左手掌中滑出。易言之。卽右手發桿。左手祗作托桿之用。重心之大部份。移寄於左腿。但非全部。因恐收勢時變化不便。且有前仆之虞。眼神亦注視桿頭。(見圖3)

Its application is to urge away an opponent’s weapon as it approaches your body.

Issuing:

Continuing from the covering posture, your right hand, going along with your waist and thighs, shoots the pole forward. The tiger’s mouth of your right hand is now upward. Your left hand makes no action, the pole sliding out within the palm. In other words, as your right hand issues the pole, your left hand is used only to prop the pole up. Most of the weight is shifted to your left leg, but not all of it, for fear that it will not be easy to switch to withdrawing, and also that you may overcommit forward. Your eyes are looking toward the pole tip. See drawing 3:

Its application is to urge away an opponent’s weapon as it approaches your body.

Issuing:

Continuing from the covering posture, your right hand, going along with your waist and thighs, shoots the pole forward. The tiger’s mouth of your right hand is now upward. Your left hand makes no action, the pole sliding out within the palm. In other words, as your right hand issues the pole, your left hand is used only to prop the pole up. Most of the weight is shifted to your left leg, but not all of it, for fear that it will not be easy to switch to withdrawing, and also that you may overcommit forward. Your eyes are looking toward the pole tip. See drawing 3:

用法乃刺敵人心窩、或喉、或肩。發時須頂懸身正。含胸拔背。沉肩垂肘。坐腰鬆胯。尾閭中正。氣沉丹田。全以腰腿之勁。而非手也。(若僅藉之以手。則桿不能有抖動之狀。)務使週身之勁。由脚、而腿、而腰、而脊、而肩、而手。以達桿頭。發出之勁。桿身自尾部起。直抖動至桿頭。其中猶如貫以水銀。發後復收囘為開。歸還原狀。開後復為合。故此三式。可循環練習。此種單式扎桿。最易長進內勁。雖不如少林派之花式衆多。然欲練至純熟。亦非易事。學者切勿漠視之。右足上步。以左手扎桿。與左足上步。以右手發者同。惟左右手相換可也。左右兩面均須練習。否則左手無勁。不能圓滿矣。學者須知拳術中。徒手練習。足以長肌肉。器械練習。足以健筋骨。故習太極拳者。徒手練習至相當程度後。則器械練習。(如刀、劍、桿子等。)不可不學也。

(註)圖中所繪之桿。因篇幅關係。故較細短。

Its application is to stab to an opponent’s solar plexus, throat, or shoulder.

When issuing, your headtop must be suspended and your body must be upright, your chest must be contained and your back must be plucked up, your shoulders must sink and your elbows must hang, your waist must lower and your hips must loosen, your tailbone must be centered, and energy must sink to your elixir field.

It is entirely a matter using the power of your waist and thighs rather than your hands. (If you only use your hands, the pole will not be able to exhibit any shaking.) Make sure to use the power of your whole body, from foot, to leg, to waist, to spine, to shoulder, to hand, all the way to the pole tip. When issuing power, it starts from the tail end of the pole and shakes straight to the tip, as though there is quicksilver coursing through it.

After issuing, withdraw to again be spreading, thereby returning to your original condition, then after spreading, again cover. These three postures can therefore be practiced in a cycle.

This type of solo thrusting pole exercise is the easiest way to develop internal power. While it is nothing like the endless flourishing postures of Shaolin, it is nevertheless not an easy task to become skillful at it, and so you must be sure not to look upon it lightly.

When your right foot is forward, use your left hand to thrust the pole, just as when your left foot is forward it is your right hand that does the issuing. It is good for your hands to be alternated with each other. Both sides must be practiced, otherwise your left hand will have no power and you will be unable to have a rounded fullness.

You must understand that within the art it is the bare-handed practice that will develop the musculature while it is the weapons training that will strengthen the sinews and bones. Therefore in the practice of Taiji Boxing, once you have reached a competent level in the bare-handed training, the weapons training (such as the saber, sword, pole, etc.) then has to be learned.

Note: Due to the space on the page, the pole in the drawings is shorter than it would actually be.

(註)圖中所繪之桿。因篇幅關係。故較細短。

Its application is to stab to an opponent’s solar plexus, throat, or shoulder.

When issuing, your headtop must be suspended and your body must be upright, your chest must be contained and your back must be plucked up, your shoulders must sink and your elbows must hang, your waist must lower and your hips must loosen, your tailbone must be centered, and energy must sink to your elixir field.

It is entirely a matter using the power of your waist and thighs rather than your hands. (If you only use your hands, the pole will not be able to exhibit any shaking.) Make sure to use the power of your whole body, from foot, to leg, to waist, to spine, to shoulder, to hand, all the way to the pole tip. When issuing power, it starts from the tail end of the pole and shakes straight to the tip, as though there is quicksilver coursing through it.

After issuing, withdraw to again be spreading, thereby returning to your original condition, then after spreading, again cover. These three postures can therefore be practiced in a cycle.

This type of solo thrusting pole exercise is the easiest way to develop internal power. While it is nothing like the endless flourishing postures of Shaolin, it is nevertheless not an easy task to become skillful at it, and so you must be sure not to look upon it lightly.

When your right foot is forward, use your left hand to thrust the pole, just as when your left foot is forward it is your right hand that does the issuing. It is good for your hands to be alternated with each other. Both sides must be practiced, otherwise your left hand will have no power and you will be unable to have a rounded fullness.

You must understand that within the art it is the bare-handed practice that will develop the musculature while it is the weapons training that will strengthen the sinews and bones. Therefore in the practice of Taiji Boxing, once you have reached a competent level in the bare-handed training, the weapons training (such as the saber, sword, pole, etc.) then has to be learned.

Note: Due to the space on the page, the pole in the drawings is shorter than it would actually be.

-

雙人平圓沾黏扎桿法

TWO-PERSON LEVEL-CIRCLE STICK & ADHERE THRUSTING POLE METHOD

TWO-PERSON LEVEL-CIRCLE STICK & ADHERE THRUSTING POLE METHOD

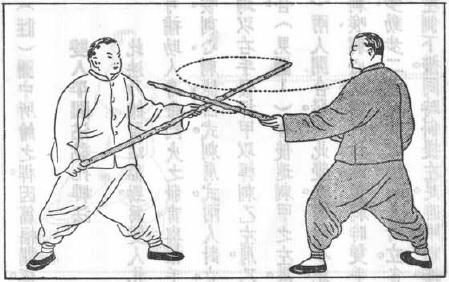

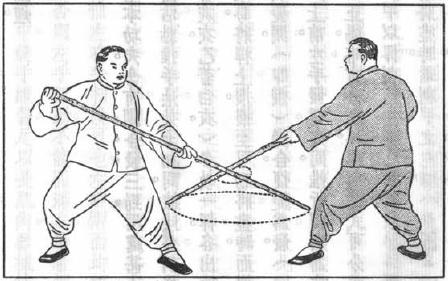

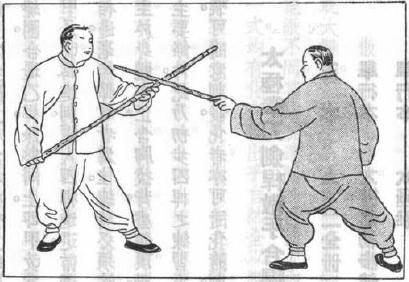

此法乃練習沾黏勁。為雙人扎桿之基本功夫。含有開、合、發、三勁。用處甚大。且可補助人身命門火之發育。與推手中平圓沾黏推手法效力相同。練法分刺肩。刺喉、刺心、刺腿、四式。刺肩式。兩人對立。(甲著灰衣。乙著白衣。)各執一桿。各出左步。均以右手發桿。甲以桿刺乙左肩。乙乘其來勢。將桿上撥。撥至甲勁將盡時。而變為合。(見圖1)

This exercise trains sticking and adhering, as well as the fundamental skill of thrusting, and contains the three energies of spreading, covering, and issuing. Its practical functions are vast, and it can assist the development of power in the lower back, having the same effects as in the level-circle stick & adhere pushing hands exercise. The techniques divide into four postures: stabbing to the shoulder, to the throat, to the solar plexus, and to the leg.

The shoulder-stabbing posture:

Two people stand facing each other (A, dressed in grey, and B, dressed in white),

each holding a pole, each stepping out with his left foot, each using his right hand to send out the pole.

A uses his pole to stab to B’s left shoulder. B goes along with the incoming momentum, sends his pole upward to deflect until A’s power has been spent, then changes to covering. See drawing 1:

This exercise trains sticking and adhering, as well as the fundamental skill of thrusting, and contains the three energies of spreading, covering, and issuing. Its practical functions are vast, and it can assist the development of power in the lower back, having the same effects as in the level-circle stick & adhere pushing hands exercise. The techniques divide into four postures: stabbing to the shoulder, to the throat, to the solar plexus, and to the leg.

The shoulder-stabbing posture:

Two people stand facing each other (A, dressed in grey, and B, dressed in white),

each holding a pole, each stepping out with his left foot, each using his right hand to send out the pole.

A uses his pole to stab to B’s left shoulder. B goes along with the incoming momentum, sends his pole upward to deflect until A’s power has been spent, then changes to covering. See drawing 1:

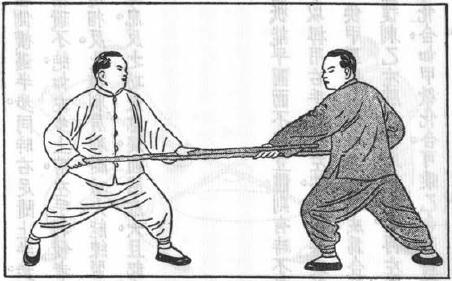

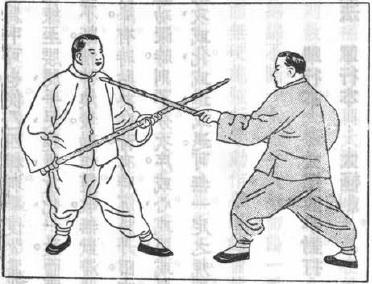

合後還刺甲之左肩。甲被刺變開。(卽撥)變合。復變為發。(卽刺)兩人開合發。彼此變換。循環不絕。如右步上前。左手發桿亦同。惟所刺則為右肩。刺喉、刺心式。亦可仿此。但刺時雙手之上下正徧。略有分別耳。至刺腿式。可分為定步、動步、二種。定步練法。兩人對立。各出左步。甲以桿刺乙左膝。乙乘其來勢將桿往左側下撥。同時斜提左足。避甲刺鋒。至甲勁將盡時。還刺甲之左膝。(見圖2)

After covering, he returns a stab to A’s left shoulder. A, now being stabbed, changes to spreading outward (i.e. deflecting), then changes to covering, then changes again to issuing (i.e. stabbing).

Both people spread, cover, and issue, alternating back and forth, recycling the exercise indefinitely. It is the same if the right foot is forward and the left hand is sending out the pole, except the stab will then be to the right shoulder.

The throat-stabbing posture or plexus-stabbing posture can also be done like this, except the hands will have to deal with the whole square, and so it is slightly different. [To clarify, when dealing with a stab to a shoulder, it needs only be deflected to the upper left or upper right, but in the case of the throat or solar plexus, being more central targets and of slightly differing heights, more attention must be given to all quadrants: upper left, upper right, lower left, lower right.]

As for the leg-stabbing posture, it can be separated into fixed-step and moving-step.

The fixed-step method:

Both people stand facing each other, each stepping out with his left foot. A uses his pole to stab to B’s left knee. B goes along with the incoming momentum and sends his pole to the lower left to deflect. At the same time, he lifts his left foot at an angle [i.e. to the upper right] to evade A’s stabbing tip. Once A’s power has been spent, B returns a stab to A’s left knee. See drawing 2:

After covering, he returns a stab to A’s left shoulder. A, now being stabbed, changes to spreading outward (i.e. deflecting), then changes to covering, then changes again to issuing (i.e. stabbing).

Both people spread, cover, and issue, alternating back and forth, recycling the exercise indefinitely. It is the same if the right foot is forward and the left hand is sending out the pole, except the stab will then be to the right shoulder.

The throat-stabbing posture or plexus-stabbing posture can also be done like this, except the hands will have to deal with the whole square, and so it is slightly different. [To clarify, when dealing with a stab to a shoulder, it needs only be deflected to the upper left or upper right, but in the case of the throat or solar plexus, being more central targets and of slightly differing heights, more attention must be given to all quadrants: upper left, upper right, lower left, lower right.]

As for the leg-stabbing posture, it can be separated into fixed-step and moving-step.

The fixed-step method:

Both people stand facing each other, each stepping out with his left foot. A uses his pole to stab to B’s left knee. B goes along with the incoming momentum and sends his pole to the lower left to deflect. At the same time, he lifts his left foot at an angle [i.e. to the upper right] to evade A’s stabbing tip. Once A’s power has been spent, B returns a stab to A’s left knee. See drawing 2:

甲被刺亦將桿往左側下撥。同時斜提左足。避乙刺鋒。兩人撥、刺。刺、撥。互相對練。動步練法。依照上法。乙在被刺撥桿時。斜提左足。向右側橫邁半步。同時右足隨上半步。刺甲膝部。甲被刺撥桿時。亦斜提左足。向右側橫邁半步。同時右足隨上半步。刺乙膝部。兩人轉成圓圈。隨轉隨撥。隨撥隨刺。循環不絕。如左步上前。左手刺發者亦同。惟兩桿相繞之圓圈。及二人旋轉之圓圈適相反。此種刺肩刺腿功夫。能練習愈深。則兩桿相遇圓圈愈小。而兩桿接觸。毫無聲息。反之功夫愈淺。圓圈愈大。且起有稜角。以致兩桿時相敲擊。聲不絕耳。

A, now being stabbed, sends his pole to the lower left to deflect. At the same time, he lifts his left foot at an angle to evade B’s stabbing tip. Both people practice deflecting and stabbing to each other, stabbing and deflecting.

The moving-step method accords with the above. When B, being stabbed, deflects with his pole and lifts his left foot at an angle, he then takes a half step across to the right side. At the same time, he advances a half step with his right foot and stabs to A’s knee.

Then A, now being stabbed, deflects with his pole, also lifting his left foot at an angle, and then takes a half step across to the right side. At the same time, he advances a half step with his right foot and stabs to B’s knee.

Both people are rotating in a circle. They turn and deflect, deflect and stab, recycling indefinitely. It is the same with the left foot forward and the left hand sending out the stab.

While the poles are winding in a circle around each other, so too are both people spinning around each other on opposite sides of a circle. When these exercises of stabbing to the shoulder or to the leg are able to be done with increasing depth of training, then the circling [of the poles] can shrink and the poles can touch without making a sound. Otherwise the skill will become shallower, their circle will become larger and start to develop corners, resulting in the poles constantly smacking into each other noisily.

A, now being stabbed, sends his pole to the lower left to deflect. At the same time, he lifts his left foot at an angle to evade B’s stabbing tip. Both people practice deflecting and stabbing to each other, stabbing and deflecting.

The moving-step method accords with the above. When B, being stabbed, deflects with his pole and lifts his left foot at an angle, he then takes a half step across to the right side. At the same time, he advances a half step with his right foot and stabs to A’s knee.

Then A, now being stabbed, deflects with his pole, also lifting his left foot at an angle, and then takes a half step across to the right side. At the same time, he advances a half step with his right foot and stabs to B’s knee.

Both people are rotating in a circle. They turn and deflect, deflect and stab, recycling indefinitely. It is the same with the left foot forward and the left hand sending out the stab.

While the poles are winding in a circle around each other, so too are both people spinning around each other on opposite sides of a circle. When these exercises of stabbing to the shoulder or to the leg are able to be done with increasing depth of training, then the circling [of the poles] can shrink and the poles can touch without making a sound. Otherwise the skill will become shallower, their circle will become larger and start to develop corners, resulting in the poles constantly smacking into each other noisily.

-

雙人立體圓形沾黏扎桿法

TWO-PERSON VERTICAL-CIRCLE STICK & ADHERE THRUSTING POLE METHOD

TWO-PERSON VERTICAL-CIRCLE STICK & ADHERE THRUSTING POLE METHOD

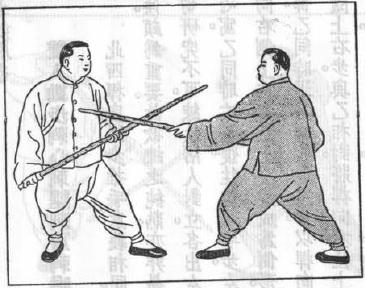

此法乃補平圓沾黏扎桿法之不足。因祗能平圓而不能立體。則有時不敷所用。易為敵所乘。練法。兩人對立。各出左步。甲以桿用右手刺乙左膝。乙乘其來勢。提起左足。將桿向下往左側撥開。(見圖1)

This exercise compensates for the insufficiencies of the level-circle method, which can only make a horizontal circle and not a vertical one, and is thus sometimes not adequately applicable and may be easy for an opponent to take advantage of.

Practice method:

Both people stand facing each other, each stepping out with his left foot. A uses his spear to stab, right-handed, to B’s left knee. B goes along with the incoming momentum, lifting his left foot and sending his pole to the lower left to deflect. See drawing 1:

This exercise compensates for the insufficiencies of the level-circle method, which can only make a horizontal circle and not a vertical one, and is thus sometimes not adequately applicable and may be easy for an opponent to take advantage of.

Practice method:

Both people stand facing each other, each stepping out with his left foot. A uses his spear to stab, right-handed, to B’s left knee. B goes along with the incoming momentum, lifting his left foot and sending his pole to the lower left to deflect. See drawing 1:

俟甲勁將盡時。將桿上繞成為合勢。(見圖2)

B waits for A’s power to be spent, then sends his pole coiling upward [and over] to make the covering posture. See drawing 2:

B waits for A’s power to be spent, then sends his pole coiling upward [and over] to make the covering posture. See drawing 2:

甲被合乘勢將桿收囘。繞一圓圈。復刺乙左膝。乙被刺。提左足。再左撥上繞。復成為合。總之。甲乙兩人。甲專刺發。乙專化合。如甲欲化合。可乘乙合勁將盡時。將桿向上翻繞。合乙桿。乙被合。隨以桿刺甲左膝。此時甲卽成為化合。乙卽成為刺發。如右足上前。左手刺發亦同。惟刺為右膝。兩人繞圈方向相反耳。此種扎桿。藝高者在一繞一合之際。能使敵連桿帶人向後離地騰出。與推手時發截勁者。有同一之妙用也。

Upon being covered, A takes advantage of the momentum and withdraws his pole,

coils a circle, then stabs again to B’s knee. B, again being stabbed, lifts his left foot, again deflecting to the left and coiling upward, and again covers downward.

To sum up both roles, A focuses on stabbing or issuing, while B focuses on neutralizing and covering. If A wants to neutralize and cover, he can take advantage of the finishing of B’s covering energy by sending his pole upward and coiling it around to cover B’s pole. B, now being covered, accordingly uses his pole to stab to A’s left knee. Now A is in the role of neutralizing and covering, while B is in the role of issuing with the stab.

If the right foot is forward, the left hand will stab in the same manner, except the stab will be to the right knee, and both people will do the coiling in the reverse direction.

One who has reached a high level in this thrusting pole exercise can, in the moment of coiling and covering, cause the opponent to be guided rearward by his connection to his own pole, leaving the ground and soaring away. It is the same trick as issuing with severing energy in the pushing hands.

Upon being covered, A takes advantage of the momentum and withdraws his pole,

coils a circle, then stabs again to B’s knee. B, again being stabbed, lifts his left foot, again deflecting to the left and coiling upward, and again covers downward.

To sum up both roles, A focuses on stabbing or issuing, while B focuses on neutralizing and covering. If A wants to neutralize and cover, he can take advantage of the finishing of B’s covering energy by sending his pole upward and coiling it around to cover B’s pole. B, now being covered, accordingly uses his pole to stab to A’s left knee. Now A is in the role of neutralizing and covering, while B is in the role of issuing with the stab.

If the right foot is forward, the left hand will stab in the same manner, except the stab will be to the right knee, and both people will do the coiling in the reverse direction.

One who has reached a high level in this thrusting pole exercise can, in the moment of coiling and covering, cause the opponent to be guided rearward by his connection to his own pole, leaving the ground and soaring away. It is the same trick as issuing with severing energy in the pushing hands.

-

雙人動步刺心刺腿刺肩刺喉四桿法

TWO-PERSON MOVING-STEP FOUR STABS TO THE SOLAR PLEXUS, LEG, SHOULDER, AND THROAT

TWO-PERSON MOVING-STEP FOUR STABS TO THE SOLAR PLEXUS, LEG, SHOULDER, AND THROAT

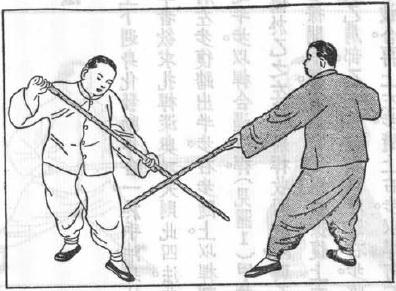

此四桿與活步推手意義相同。亦求上下週身化發動作合一。於手法、身法、步法。頗為重要。故欲練之純熟。亦非易事。然學者欲求扎桿深奧功夫。則此四法。非深切研究不可。練法。兩人對立。各出左步。甲將左步復踏出半步。右步隨上。以桿刺乙心窩。乙同時右足復往後退半步。左足收進半步。以桿合逼甲桿。(見圖1)

These four pole techniques share the same aim as the moving-step pushing hands, that your upper body and lower, while neutralizing or issuing, are to move as a single unit. Since the hand methods, body methods, and stepping methods are all crucial, to train to the point of skillfulness is not an easy task. Yet if you do wish for depth of skill in the thrusting pole techniques, it cannot be attained without deeply studying this four-part exercise.

Practice method:

Both people stand facing each other, each stepping out with his left foot. A sends his left foot out another half step, his right foot following forward, as he uses his pole to stab to B’s solar plexus.

B at the same time retreats his right foot a half step, his left foot also withdrawing a half step, as he uses his pole to cover and urge away A’s pole. See drawing 1:

These four pole techniques share the same aim as the moving-step pushing hands, that your upper body and lower, while neutralizing or issuing, are to move as a single unit. Since the hand methods, body methods, and stepping methods are all crucial, to train to the point of skillfulness is not an easy task. Yet if you do wish for depth of skill in the thrusting pole techniques, it cannot be attained without deeply studying this four-part exercise.

Practice method:

Both people stand facing each other, each stepping out with his left foot. A sends his left foot out another half step, his right foot following forward, as he uses his pole to stab to B’s solar plexus.

B at the same time retreats his right foot a half step, his left foot also withdrawing a half step, as he uses his pole to cover and urge away A’s pole. See drawing 1:

甲被合。向右側上右步。隨上左步。成為側形。(卽甲偏於乙之左邊)將桿收囘繞圈。刺乙腿部。乙同時退右步。收進左步。以桿向下往右撩開甲桿。(見圖2)

A, now being covered, steps his right foot forward to the right side, his left foot then stepping forward, making a side-angled posture (i.e. A inclined toward B’s left side), while withdrawing his pole, coiling it around, and stabbing to B’s [left] leg.

B at the same time retreats his right foot, withdrawing his left foot, as he sends his pole to the lower right to lift away A’s pole. See drawing 2:

A, now being covered, steps his right foot forward to the right side, his left foot then stepping forward, making a side-angled posture (i.e. A inclined toward B’s left side), while withdrawing his pole, coiling it around, and stabbing to B’s [left] leg.

B at the same time retreats his right foot, withdrawing his left foot, as he sends his pole to the lower right to lift away A’s pole. See drawing 2:

甲被撩。復上左步。隨上右步。與乙相對。將桿向左往上繞圈。刺乙肩部。乙在將被刺到時。退右步。收進左步。以桿向上繞圈。合逼甲桿。(見圖3)

A, now being lifted, steps his left foot forward, his right foot following, to be directly facing B, while sending his pole coiling to the upper left and stabbing to B’s [left] shoulder.

When B is about to be stabbed, he retreats his right foot, his left foot withdrawing, while sending his pole coiling upward to cover and urge away A’s pole. See drawing 3:

A, now being lifted, steps his left foot forward, his right foot following, to be directly facing B, while sending his pole coiling to the upper left and stabbing to B’s [left] shoulder.

When B is about to be stabbed, he retreats his right foot, his left foot withdrawing, while sending his pole coiling upward to cover and urge away A’s pole. See drawing 3:

甲被合。再上左步。隨上右步。以桿向右往後繞圈。化開乙桿。復刺其喉。乙在將被刺到時。退右步。收進左步。以桿繞圈合逼甲桿。(見圖4)

A, now being covered, again steps his left foot forward, his right foot following, while coiling his pole to the right rear to neutralize and spread away B’s pole, then stabs to his throat.

When B is about to be stabbed, he retreats his right foot, his left foot withdrawing, while coiling his pole to cover and urge away A’s pole. See drawing 4:

A, now being covered, again steps his left foot forward, his right foot following, while coiling his pole to the right rear to neutralize and spread away B’s pole, then stabs to his throat.

When B is about to be stabbed, he retreats his right foot, his left foot withdrawing, while coiling his pole to cover and urge away A’s pole. See drawing 4:

如是甲進步四桿已畢。以後改為退步。乙則改為進步。乙在化甲刺喉後。上左步。隨上右步。以桿往上繞圈刺甲心窩。甲同時退右步。收進左步。將桿向上繞圈。合逼乙桿。餘勢同上。卽甲改為乙。乙改為甲可也。俟乙四桿刺畢。復改為化退。甲又改為進刺。兩人四桿進退。循環練習。須練至腰腿、手足、進退、攻化、一致。而兩桿相遇。毫無聲息者為佳。練時必須注意內勁不斷。精神煥發。動作靈敏。無獃滯狀態。至於身體中正。含胸拔背。虛領頂勁。氣之升降。有時貼於脊背。有時沉於丹田。亦為主要條件。此乃初步四桿之練習方法。若至功深時。則不分次序。或心、或腿、或肩、或喉。可隨意刺發。化者亦可隨化隨刺。總之。或攻、或化、或進、或退。可無一定之規則也。

When A completes his four stabs, he then switches to retreating and B switches to advancing. After B has neutralized A’s stab to the throat, he steps his left foot forward, his right foot following, while coiling his pole upward and stabbing to A’s solar plexus.

A at the same time retreats his right foot, his left foot withdrawing, while sending his pole coiling upward to cover and urge away B’s pole. The rest of the postures are the same as above, except A is to be read as B, and B to be read as A. Once B has completed his four stabs, he then switches to again be neutralizing and retreating, and A switches to again be advancing and stabbing. Both people do their four actions, advancing and retreating, recycling the exercise over and over.

It must be drilled until waist and thigh, hand and foot, advance and retreat, and attack and neutralize are unified. And when both poles are making contact without the slightest sound or pause, that is best. When practicing, you must pay attention that your internal power does not get interrupted, your spirit expresses with potency, your movement is nimble, and your posture is without any awkward sluggishness. Your body is to be balanced and upright, your chest contained and back plucked up, and your headtop pressing up forcelessly. Energy ascends and descends, one moment sticking to your spine, one moment sinking to your elixir field. These are the crucial factors.

This is the beginning method of practicing these four techniques. When skill has deepened, then you no longer need to be particular about the sequence. Whether to the solar plexus, leg, shoulder, or throat, the stab can be issued to wherever you please, and the one who is neutralizing can do so according to the stab. Ultimately, whether attacking or neutralizing, advancing or retreating, all can be done without a set pattern.

When A completes his four stabs, he then switches to retreating and B switches to advancing. After B has neutralized A’s stab to the throat, he steps his left foot forward, his right foot following, while coiling his pole upward and stabbing to A’s solar plexus.

A at the same time retreats his right foot, his left foot withdrawing, while sending his pole coiling upward to cover and urge away B’s pole. The rest of the postures are the same as above, except A is to be read as B, and B to be read as A. Once B has completed his four stabs, he then switches to again be neutralizing and retreating, and A switches to again be advancing and stabbing. Both people do their four actions, advancing and retreating, recycling the exercise over and over.

It must be drilled until waist and thigh, hand and foot, advance and retreat, and attack and neutralize are unified. And when both poles are making contact without the slightest sound or pause, that is best. When practicing, you must pay attention that your internal power does not get interrupted, your spirit expresses with potency, your movement is nimble, and your posture is without any awkward sluggishness. Your body is to be balanced and upright, your chest contained and back plucked up, and your headtop pressing up forcelessly. Energy ascends and descends, one moment sticking to your spine, one moment sinking to your elixir field. These are the crucial factors.

This is the beginning method of practicing these four techniques. When skill has deepened, then you no longer need to be particular about the sequence. Whether to the solar plexus, leg, shoulder, or throat, the stab can be issued to wherever you please, and the one who is neutralizing can do so according to the stab. Ultimately, whether attacking or neutralizing, advancing or retreating, all can be done without a set pattern.

-

楊家小傳

*BRIEF YANG FAMILY BIOGRAPHIES

*BRIEF YANG FAMILY BIOGRAPHIES

[YANG LUCHAN]

楊福魁、字露禪。一曰祿纏。河北省(昔直隸)廣平府永年縣人。幼時至河南陳家溝。從陳長興學習太極拳術。陳立身中正。不倚不靠。狀如木雞。人稱為牌位先生。其時從陳習拳者。皆陳族人。異姓惟楊與其同里李伯魁二人而已。故陳姓頗岐視之。因是楊居陳家數載。無所得。一夜楊醒。聞隔院有哼哈之聲。遂起越垣。見廣廈數間。哼哈之聲。卽由此而出。乃破牆隙窺之。(迄今古跡尚在)瞥見其師正教諸徒拿發諸術。大奇。自是每夜必往窺。與李互相結納。悉心研究。功夫乃大進。後陳命楊與諸徒决。徒皆敗北。陳始驚楊為天才。遂盡受其祕術焉。楊歸。傳授同里之人。從學者甚衆。當時稱楊拳為化拳。或曰綿拳。以其動作綿而能化也。後至北平。(昔北京)清代王公貝勒等從其習學者頗多。旋為旗營武術教師。性剛強。勿論何門何派。均喜與比試。嘗身負一小花鎗及一小包裹。遍遊華北諸省。凡所至之地。聞有藝高者。輒拜訪與之較量。卽有人自認弗敵。亦必強與之較。但未嘗傷人。因武藝高超。所向無敵。故世稱「楊無敵」云。楊生於嘉慶四年。卒於同治十一年。生三子。長曰錡。早亡。次曰鈺。三曰鑑。皆能傳父業。楊之生平軼事甚多。茲摘錄數則於後。

楊在廣平時。嘗與人鬬於城上。其人不敵。直退至城牆邊緣。足立不穩。身隨勢後傾。將墜落。於此千鈞一髮之際。楊忽於二三丈外。陡躍而前。攀握其足。得不墜死。

楊善用鎗桿。物之輕者。經桿一沾濡。可卽起。無稍失。其救火輒以桿頭撥牆垣。使火勢不致蔓延。且能在馬上不用弓絃。僅以手指投箭。百無一失。亦絕技也。

一日天雨。楊坐堂上。見其女捧銅盆自外入。比及階。簾未揭也。而苔痕澝滑。女足適跛蹶。楊卽一躍而出。一手揭簾。一手扶女臂。女旣未仆。而盆中之水。亦竟涓滴未傾。其功力之神異。卽小見大。於此可見一斑矣。

又一日。楊釣於河畔。有外家名拳師二人。適於楊之背後過。因素震其名。獨不敢與之當面較。今見楊正垂釣。以為有機可乘。擬從楊後推其背。使顚覆溺水。以損其名。乃相約躡足左右。同時疾趨以為進襲。詎楊眼梢特長。已早審知有人暗算。於二人手猛力到時。遽以含胸拔背。高探馬一式之法。惟見其背一隆。首一叩。二人同時被擲河中。乃曰。今日便宜汝等。否則若在地上。將欲再加一手。二人聞言。倉皇泅水而逝。

Yang Fukui, called Luchan (with two variations of the characters for this pronunciation, meaning in one case “Revealed Zen” and meaning in the other case “Luck Entwined”),

was from Hebei (which was called Zhili in his time).

When he was young, he went to the Chen family village in Henan to learn the Taiji boxing art from Chen Changxing. Chen’s body stood centered and upright, not leaning in any direction. He was as expressionless as a rooster made of wood, and so people called him “Mr. Board”.

While he was learning the boxing from Chen, everyone else there was a native of the Chen family line. The only two people with a surname that was not Chen were Yang and his hometown companion Li Bokui, and so there was a bias toward those surnamed Chen. Because of this, Yang dwelled for several years in the Chen village without gaining anything.

One night he awoke to hear sounds of “heng!” and “ha!” coming from the courtyard. He climbed up to look over the wall and saw between several of the buildings where the sounds were coming from. He then [came down and] peeked through a crack in the wall (the historic site of which still exists), glimpsing Chen giving his students corrections in the skill of seizing and issuing, an amazing sight.

From that point on, he had to observe every night. By meticulously working with Li on the material he observed, great progress was made. Later when Chen called upon Yang to be tested against his students, they were all defeated. Chen began to be surprised by Yang’s talent and thereupon taught him all his secrets.

When Yang returned home, he taught it to his fellow villagers, and a great many students learned from him. At that time Yang’s boxing was known as Neutralization Boxing and was also called Silken Boxing, for his movements were continuous and adaptable.

He then went to Beiping (called Beijing in his time). [Beijing was briefly renamed Beiping from fifteen years before Chen’s book was published until six years after, since throughout that time the Chinese capital or “jing” was actually Nanjing.] Quite a few of his students were Qing Dynasty nobles and so he was soon appointed as the martial arts instructor to the Manchu barracks.

Being of an indomitable temperament, he was happy to compete with anyone regardless of style. He took a trip around the northern provinces, hoboing around shouldering a short spear and a small wrapped bundle. Wherever he ended up, he heard about the local highly skilled and paid them visits to try them out. Some acknowledged they were not his equal, while others insisted on struggling against him, and yet he never injured any of them. Because his martial skill was the highest, he met no match. Therefore his generation dubbed him “Yang the Invincible”.

Yang was born in the fourth year of the reign of Emperor Jiaqing [1799] and died in the eleventh year of the reign of Emperor Tongzhi [1872]. He had three sons, the eldest named Qi, who died young, the second named Yu [Banhou], and the third named Jian [Jianhou]. The two surviving sons were both capable in passing on their father’s teachings.

There are a great many anecdotes about Yang’s experiences during his life. Here are but a select few:

When Yang was in Guangping, he had a bout with a man atop a wall. But the man was no match for him, backing up right onto the wall’s edge where there was no stability to his footing, his body leaning back, and he was about to fall. At this moment of precariousness, Yang had ended up some twenty or thirty feet away from him [because of the speed of the man’s retreat], yet suddenly he had leapt forward and seized the man’s foot to keep him from falling to his death.

Yang was an expert at using the spear. To show his dexterity with it, he would immerse the shaft in liquid, and could then lift it out without it being at all wet. To fight a fire, he used the head of the shaft to brush down a wall and prevent the fire from spreading. He also had the ability while on horseback to send an arrow without using a bow, just his fingers, and hit the target every time, so superb were his skills.

One rainy day, Yang was sitting in the main hall [of his house] and he saw his daughter carrying in a bronze basin [full of water]. She had gotten up the main steps, but the curtain at the entranceway had not yet been drawn aside and there was some slippery moss, upon which her foot slid out from under her and she fell. Yang came out in a single bound, drawing open the curtain with one hand while with the other he supported her arm. Neither did she fall nor had a single drop of water fallen from the basin. His skill was magical, magnifying ordinary events such as these into extraordinary ones.

Another day, Yang was fishing beside a river. Two famous teachers of external styles happened to be passing along behind Yang. Due to his intimidating prestige, they would never dare to compete against him face to face. But now they saw Yang was occupied with dangling his fishing hook and took this as an opportunity. They planned to creep up behind him and push him into the river, thereby ruining his reputation. They agreed to tiptoe along, one on the left and one on the right, and then rush him in unison with a surprise attack. From Yang’s peripheral vision, he already knew there were people plotting against him, and so when the two men’s hands forcefully arrived, he suddenly hollowed his chest and plucked up his back, as in the posture of “Rising Up and Reaching Out to the Horse”. They only saw his back bulge and his head bow forward, and then both men had been thrown together into the river. Then Yang told them: “Today is your lucky day. If you guys were on the ground with me, I would want to give you a beating.” The two men heard his words, then hurriedly swam away until they were gone from sight.

楊在廣平時。嘗與人鬬於城上。其人不敵。直退至城牆邊緣。足立不穩。身隨勢後傾。將墜落。於此千鈞一髮之際。楊忽於二三丈外。陡躍而前。攀握其足。得不墜死。

楊善用鎗桿。物之輕者。經桿一沾濡。可卽起。無稍失。其救火輒以桿頭撥牆垣。使火勢不致蔓延。且能在馬上不用弓絃。僅以手指投箭。百無一失。亦絕技也。

一日天雨。楊坐堂上。見其女捧銅盆自外入。比及階。簾未揭也。而苔痕澝滑。女足適跛蹶。楊卽一躍而出。一手揭簾。一手扶女臂。女旣未仆。而盆中之水。亦竟涓滴未傾。其功力之神異。卽小見大。於此可見一斑矣。

又一日。楊釣於河畔。有外家名拳師二人。適於楊之背後過。因素震其名。獨不敢與之當面較。今見楊正垂釣。以為有機可乘。擬從楊後推其背。使顚覆溺水。以損其名。乃相約躡足左右。同時疾趨以為進襲。詎楊眼梢特長。已早審知有人暗算。於二人手猛力到時。遽以含胸拔背。高探馬一式之法。惟見其背一隆。首一叩。二人同時被擲河中。乃曰。今日便宜汝等。否則若在地上。將欲再加一手。二人聞言。倉皇泅水而逝。

Yang Fukui, called Luchan (with two variations of the characters for this pronunciation, meaning in one case “Revealed Zen” and meaning in the other case “Luck Entwined”),

was from Hebei (which was called Zhili in his time).

When he was young, he went to the Chen family village in Henan to learn the Taiji boxing art from Chen Changxing. Chen’s body stood centered and upright, not leaning in any direction. He was as expressionless as a rooster made of wood, and so people called him “Mr. Board”.

While he was learning the boxing from Chen, everyone else there was a native of the Chen family line. The only two people with a surname that was not Chen were Yang and his hometown companion Li Bokui, and so there was a bias toward those surnamed Chen. Because of this, Yang dwelled for several years in the Chen village without gaining anything.

One night he awoke to hear sounds of “heng!” and “ha!” coming from the courtyard. He climbed up to look over the wall and saw between several of the buildings where the sounds were coming from. He then [came down and] peeked through a crack in the wall (the historic site of which still exists), glimpsing Chen giving his students corrections in the skill of seizing and issuing, an amazing sight.

From that point on, he had to observe every night. By meticulously working with Li on the material he observed, great progress was made. Later when Chen called upon Yang to be tested against his students, they were all defeated. Chen began to be surprised by Yang’s talent and thereupon taught him all his secrets.

When Yang returned home, he taught it to his fellow villagers, and a great many students learned from him. At that time Yang’s boxing was known as Neutralization Boxing and was also called Silken Boxing, for his movements were continuous and adaptable.

He then went to Beiping (called Beijing in his time). [Beijing was briefly renamed Beiping from fifteen years before Chen’s book was published until six years after, since throughout that time the Chinese capital or “jing” was actually Nanjing.] Quite a few of his students were Qing Dynasty nobles and so he was soon appointed as the martial arts instructor to the Manchu barracks.

Being of an indomitable temperament, he was happy to compete with anyone regardless of style. He took a trip around the northern provinces, hoboing around shouldering a short spear and a small wrapped bundle. Wherever he ended up, he heard about the local highly skilled and paid them visits to try them out. Some acknowledged they were not his equal, while others insisted on struggling against him, and yet he never injured any of them. Because his martial skill was the highest, he met no match. Therefore his generation dubbed him “Yang the Invincible”.

Yang was born in the fourth year of the reign of Emperor Jiaqing [1799] and died in the eleventh year of the reign of Emperor Tongzhi [1872]. He had three sons, the eldest named Qi, who died young, the second named Yu [Banhou], and the third named Jian [Jianhou]. The two surviving sons were both capable in passing on their father’s teachings.

There are a great many anecdotes about Yang’s experiences during his life. Here are but a select few:

When Yang was in Guangping, he had a bout with a man atop a wall. But the man was no match for him, backing up right onto the wall’s edge where there was no stability to his footing, his body leaning back, and he was about to fall. At this moment of precariousness, Yang had ended up some twenty or thirty feet away from him [because of the speed of the man’s retreat], yet suddenly he had leapt forward and seized the man’s foot to keep him from falling to his death.

Yang was an expert at using the spear. To show his dexterity with it, he would immerse the shaft in liquid, and could then lift it out without it being at all wet. To fight a fire, he used the head of the shaft to brush down a wall and prevent the fire from spreading. He also had the ability while on horseback to send an arrow without using a bow, just his fingers, and hit the target every time, so superb were his skills.

One rainy day, Yang was sitting in the main hall [of his house] and he saw his daughter carrying in a bronze basin [full of water]. She had gotten up the main steps, but the curtain at the entranceway had not yet been drawn aside and there was some slippery moss, upon which her foot slid out from under her and she fell. Yang came out in a single bound, drawing open the curtain with one hand while with the other he supported her arm. Neither did she fall nor had a single drop of water fallen from the basin. His skill was magical, magnifying ordinary events such as these into extraordinary ones.

Another day, Yang was fishing beside a river. Two famous teachers of external styles happened to be passing along behind Yang. Due to his intimidating prestige, they would never dare to compete against him face to face. But now they saw Yang was occupied with dangling his fishing hook and took this as an opportunity. They planned to creep up behind him and push him into the river, thereby ruining his reputation. They agreed to tiptoe along, one on the left and one on the right, and then rush him in unison with a surprise attack. From Yang’s peripheral vision, he already knew there were people plotting against him, and so when the two men’s hands forcefully arrived, he suddenly hollowed his chest and plucked up his back, as in the posture of “Rising Up and Reaching Out to the Horse”. They only saw his back bulge and his head bow forward, and then both men had been thrown together into the river. Then Yang told them: “Today is your lucky day. If you guys were on the ground with me, I would want to give you a beating.” The two men heard his words, then hurriedly swam away until they were gone from sight.

[YANG BANHOU]

鈺、字班侯。人皆呼為二先生。生於道光十七年。幼隨父習太極拳術。終日孜孜苦練。不間寒暑。然其父猶不使少息。且備受鞭撻。幾至逃亡。性剛強。善用散手。喜發人。往往出手見紅。被擊者常跌出三丈六尺之外。其功力火候。備臻上乘。惜不願多傳門人。以致曲高和寡。終成絕調。良可慨矣。卒於光緒十六年。遺子一。名兆鵬。

Yang Yu, called Banhou, known by all as “Second Teacher”, was born in the seventeenth year of the reign of Emperor Daoguang [1837].

When he was young, he practiced the Taiji boxing art in accordance with his father.

He trained very hard all day long, without any pause even during days of winter or summer, for his father would not allow him to take any break. He endured several beatings with a stick, until finally he tried to run away from home.

He had an unyielding personality and was an expert at sparring. He enjoyed throwing people and they were frequently seen to be bruised when he sent out his hands at them. Those who had been hit by him often fell more than thirty feet away.

His skill was of such a degree that he attained the highest level. Unfortunately he was not willing to teach many people, with the result that very few comprehended what he was doing, and ultimately we can only sigh at his achievement.

He died in the sixteenth year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu [1890], leaving one son, named Zhaopeng.

Yang Yu, called Banhou, known by all as “Second Teacher”, was born in the seventeenth year of the reign of Emperor Daoguang [1837].

When he was young, he practiced the Taiji boxing art in accordance with his father.

He trained very hard all day long, without any pause even during days of winter or summer, for his father would not allow him to take any break. He endured several beatings with a stick, until finally he tried to run away from home.

He had an unyielding personality and was an expert at sparring. He enjoyed throwing people and they were frequently seen to be bruised when he sent out his hands at them. Those who had been hit by him often fell more than thirty feet away.

His skill was of such a degree that he attained the highest level. Unfortunately he was not willing to teach many people, with the result that very few comprehended what he was doing, and ultimately we can only sigh at his achievement.

He died in the sixteenth year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu [1890], leaving one son, named Zhaopeng.

[YANG JIANHOU]

鑑、字健侯。號鏡湖。人呼為三先生。晚年後人呼為老先生。生於道光二十二年。練工亦在幼時。其父嚴厲。終日督視。不使少怠。以致身心疲敝。不能勝任。曾擬雉經數次。幸均被覺。未果。可見當時練功之刻苦精神。卒能成其大名。性較兄柔和。從業者甚衆。教習大中小三種架子皆備。其功剛柔並濟。已臻大成。當時他派中有善用刀劍者。與之交手。健侯僅以拂塵挫敵。每一搭手。多被擒拿。處於背勢。而不能近其身。又善用槍桿。任何勁力。均可發於桿頭。他人槍桿遇之。無不連人帶桿同時跌出。其週身皆能發人。而發勁輒在一笑一哈之頃。且善發彈。發無不中。三四彈在手中。往往能同時射擊三四飛鳥。尤奇者。止燕雀於彼掌心中。不能飛去。蓋因鳥類在將飛前。兩足必先下沉。沉後得勢。方可聳身上飛。楊能聽其兩爪下沉之勁。隨之往下鬆化。則燕雀因無力可借。故不能聳身飛去。由此可知彼聽勁與化勁之靈敏奇妙。絕非他人所能望其項背也。晚年練工。常在臥時。衣不解帶。倏忽卽醒。夜深時。侍者常聞其臥床作抖動之奇聲。卒於民國六年。無病而逝。在臨危前數小時。得一夢兆。知將死。呼家人及生徒至。一一叮囑。屆時沐浴更衣。含笑而終。有三子。長曰兆熊。次曰兆元。早亡。三曰兆清。

Yang Jian, called Jianhou, as well as Jinghu, was called by people “Third Teacher”, and called by the succeeding generation during his later years “Old Teacher”. He was born in the twenty-second year of the reign of Emperor Daoguang [1842]

While training in the art during his youth, his father was very strict, keeping an eye on him all day long and never allowing him the slightest slackness, until finally he was exhausted in body and mind and could bear it no longer. He tried to hang himself several times, but fortunately was discovered before succeeding at it. From this can be gleaned the arduous training mentality of those days, from which he was ultimately able to achieve great fame.

He had a more gentle temperament than his brother and so his services were engaged by a great many. He was able to teach all three sizes of the solo set – large frame, medium frame, small frame – and was skillful at both hardness and softness equally, such was the grand level of his attainment.

Other areas of his expertise at that time included saber, sword, and sparring. He once used only a horsetail duster to defeat a [saber-wielding] opponent. [During hand-to-hand sparring,] with every touch of his hand, an opponent was usually seized and made to back away, unable to get near his body.

He was also an expert at using the spear. However strong an opponent was, he could always fling the man’s spear tip up so he would encounter his own spear and invariably be caused to fall down with it. He could shoot opponents away with any part of his body, and whenever he issued power upon them he would then giggle for a little while.

He was also an expert with a pellet bow, with which he always hit the target. With three or four pellets in his hand, he often could shoot them all at the same time and hit just as many birds at once.

Most marvelous of all, he could put a finch on his palm and it was unable to fly away. This is because when a bird is about to take flight, its feet must first sink downward to then gain the power to be able to raise its body up and fly. But Yang could listen to the sinking energy of its feet and go along with it downward to neutralize it. Since the bird could not borrow power from anywhere, it was thus unable to raise its body and fly away. From this can be known the keen sensitivity of his listening and neutralizing, and why other people were unable to catch up to his level.

He continued to practice his skills in his later years. He would often sleep on his back without undressing, then suddenly awake fully alert. In the middle of the night, servants would often hear the peculiar noise of his bed trembling when he awoke.

He died in the sixth year of the Republic [1917], passing away without illness. Several hours before he died, he had a portentous dream and knew he was about to die. He called for his family members and students to be there, and one by one he gave them encouragements. At the appointed time, he bathed and put on fresh clothes, then smiled and passed away. He had three sons, the eldest named Zhaoxiong [Shaohou], the second named Zhaoyuan, who died young, and the third named Zhaoqing [Chengfu].

Yang Jian, called Jianhou, as well as Jinghu, was called by people “Third Teacher”, and called by the succeeding generation during his later years “Old Teacher”. He was born in the twenty-second year of the reign of Emperor Daoguang [1842]

While training in the art during his youth, his father was very strict, keeping an eye on him all day long and never allowing him the slightest slackness, until finally he was exhausted in body and mind and could bear it no longer. He tried to hang himself several times, but fortunately was discovered before succeeding at it. From this can be gleaned the arduous training mentality of those days, from which he was ultimately able to achieve great fame.

He had a more gentle temperament than his brother and so his services were engaged by a great many. He was able to teach all three sizes of the solo set – large frame, medium frame, small frame – and was skillful at both hardness and softness equally, such was the grand level of his attainment.

Other areas of his expertise at that time included saber, sword, and sparring. He once used only a horsetail duster to defeat a [saber-wielding] opponent. [During hand-to-hand sparring,] with every touch of his hand, an opponent was usually seized and made to back away, unable to get near his body.

He was also an expert at using the spear. However strong an opponent was, he could always fling the man’s spear tip up so he would encounter his own spear and invariably be caused to fall down with it. He could shoot opponents away with any part of his body, and whenever he issued power upon them he would then giggle for a little while.

He was also an expert with a pellet bow, with which he always hit the target. With three or four pellets in his hand, he often could shoot them all at the same time and hit just as many birds at once.

Most marvelous of all, he could put a finch on his palm and it was unable to fly away. This is because when a bird is about to take flight, its feet must first sink downward to then gain the power to be able to raise its body up and fly. But Yang could listen to the sinking energy of its feet and go along with it downward to neutralize it. Since the bird could not borrow power from anywhere, it was thus unable to raise its body and fly away. From this can be known the keen sensitivity of his listening and neutralizing, and why other people were unable to catch up to his level.

He continued to practice his skills in his later years. He would often sleep on his back without undressing, then suddenly awake fully alert. In the middle of the night, servants would often hear the peculiar noise of his bed trembling when he awoke.

He died in the sixth year of the Republic [1917], passing away without illness. Several hours before he died, he had a portentous dream and knew he was about to die. He called for his family members and students to be there, and one by one he gave them encouragements. At the appointed time, he bathed and put on fresh clothes, then smiled and passed away. He had three sons, the eldest named Zhaoxiong [Shaohou], the second named Zhaoyuan, who died young, and the third named Zhaoqing [Chengfu].

[YANG SHAOHOU]

兆熊、字夢祥。晚字少侯。後人呼為大先生。生於同治元年。七歲時卽習太極拳術。性剛強。亦喜發人。善用散手。有乃伯遺風。功屬上乘。拳架小而剛。動作快而沉。處處求緊凑。其教人亦然。因好出手卽攻。學者多不能受。故從學甚少。彼對於借勁、冷勁、截勁、凌空勁。確有深功。惜不願多傳。故知之者稀。卒於民國十八年。有子一。名振聲。

Yang Zhaoxiong, called Mengxiang, later called Shaohou, and called “Great Teacher” by the succeeding generation, was born in the first year of the reign of Emperor Tongzhi [1862].

Once he was seven years old, he trained in the Taiji boxing art. He had an unyielding personality, enjoyed throwing people, and was an expert at sparring. Having been taught by his uncle [Yang Banhou], his skill was also at the highest level.

His boxing set was small and hard, the movements fast and heavy, and he always strived for compactness. He was also thus when teaching people, and because he so enjoyed attacking, his students often could not endure it, and therefore he taught very few.

He had a truly deep skill in regard to the energies of borrowing, stiffening, severing, and traversing emptiness, but unfortunately he was not willing to teach many people, and so those who comprehend what he was doing are rare.

He died in the eighteenth year of the Republic [1929]. He had one son, named Zhensheng.

Yang Zhaoxiong, called Mengxiang, later called Shaohou, and called “Great Teacher” by the succeeding generation, was born in the first year of the reign of Emperor Tongzhi [1862].

Once he was seven years old, he trained in the Taiji boxing art. He had an unyielding personality, enjoyed throwing people, and was an expert at sparring. Having been taught by his uncle [Yang Banhou], his skill was also at the highest level.

His boxing set was small and hard, the movements fast and heavy, and he always strived for compactness. He was also thus when teaching people, and because he so enjoyed attacking, his students often could not endure it, and therefore he taught very few.

He had a truly deep skill in regard to the energies of borrowing, stiffening, severing, and traversing emptiness, but unfortunately he was not willing to teach many people, and so those who comprehend what he was doing are rare.

He died in the eighteenth year of the Republic [1929]. He had one son, named Zhensheng.

[YANG CHENGFU]

兆清、字澄甫。後人呼為三先生。生於光緒九年。性温和。幼時不甚喜拳擊。年將弱冠。始從父學。父在。亦未深研拳中奧妙。父逝後。頓起覺悟。日夜苦練。終負盛譽。各種功夫。却由自研而得。誠絕頂聰慧之天才。如能在幼時悉心從父學習。則其造就。當不在乃祖下矣。身材魁梧。外軟如棉。內堅如鐵。引人發人。均臻上乘。其教人多屬大架子。以求姿勢大開大展。適與乃兄相反。因性情和順。從業者衆。譽遍南北。卒於民國二十四年。有四子。長曰振銘。次曰振基。三曰振鐸。四曰振國。

Yang Zhaoqing, called Chengfu, and called “Third Teacher” by the succeeding generation, was born in the ninth year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu [1883].

He had a mild disposition. When he was young, he was not very interested in boxing arts. He came to adulthood as a weakling, and so he started learning from his father. While his father was alive, he had not yet deeply studied the art’s subtleties, but after his father had passed away, he suddenly awakened to it and practiced diligently day and night, ultimately enjoying a flourishing fame in all of its skills.

Seeing as he obtained it through self study, he truly was gifted with a remarkable intelligence. Yet if he could have carefully learned from his father from when he was young, then his achievement would have been accelerated and would not have turned out inferior to his grandfather’s.

His stature was big and tall. Outwardly he was soft as cotton, but inside he was hard as iron. Whether drawing opponents in or launching opponents away, in both he had attained the highest level.

The boxing set he taught people was usually the large frame, seeking for the postures to be greatly opened up and spread out, completely the opposite of his brother. Because his personality was so amiable, his services were engaged by a great many, and he was praised everywhere from north to south.

He died in the twenty-fourth year of the Republic [1935]. He had four sons, the eldest named Zhenming, the second named Zhenji, the third named Zhenduo, and the fourth named Zhenguo.

Yang Zhaoqing, called Chengfu, and called “Third Teacher” by the succeeding generation, was born in the ninth year of the reign of Emperor Guangxu [1883].

He had a mild disposition. When he was young, he was not very interested in boxing arts. He came to adulthood as a weakling, and so he started learning from his father. While his father was alive, he had not yet deeply studied the art’s subtleties, but after his father had passed away, he suddenly awakened to it and practiced diligently day and night, ultimately enjoying a flourishing fame in all of its skills.

Seeing as he obtained it through self study, he truly was gifted with a remarkable intelligence. Yet if he could have carefully learned from his father from when he was young, then his achievement would have been accelerated and would not have turned out inferior to his grandfather’s.

His stature was big and tall. Outwardly he was soft as cotton, but inside he was hard as iron. Whether drawing opponents in or launching opponents away, in both he had attained the highest level.

The boxing set he taught people was usually the large frame, seeking for the postures to be greatly opened up and spread out, completely the opposite of his brother. Because his personality was so amiable, his services were engaged by a great many, and he was praised everywhere from north to south.

He died in the twenty-fourth year of the Republic [1935]. He had four sons, the eldest named Zhenming, the second named Zhenji, the third named Zhenduo, and the fourth named Zhenguo.

綜之。今人言太極拳。無不推崇楊氏。著者述楊氏三代祖孫小傳于此。有世代隆替之興感。大凡藝事。往往一代遜於一代。拳術亦然。以楊氏論。則露禪可謂登峯造極。莫與之京。然傳至其子已較遜。傳至其孫而愈遜。今少侯澄甫子。亦各得遺傳。幸其子孫。克繩祖武。黽勉有加。則楊氏令名。得以保存矣。

Generally when people nowadays discuss Taiji Boxing, they all highly praise the Yang family. In the brief bios of the three generations of the Yang family which I have supplied here, there is a sense of a rise and fall through the generations. In all arts, it is often the case that one generation is inferior to another, and this is also the case with boxing arts.

Regarding the Yang family, Yang Luchan can be considered to have climbed to the highest peak, incomparable. Although it was passed down to his sons, they were in comparison inferior, and then it was passed down to his grandsons, who were more inferior still. Presently it is the sons of Shaohou and Chengfu who have also inherited the transmission. I hope these descendants prove able to continue their ancestors’ achievements, and if they exert themselves that much more, then the Yang family’s reputation can be preserved.

Generally when people nowadays discuss Taiji Boxing, they all highly praise the Yang family. In the brief bios of the three generations of the Yang family which I have supplied here, there is a sense of a rise and fall through the generations. In all arts, it is often the case that one generation is inferior to another, and this is also the case with boxing arts.

Regarding the Yang family, Yang Luchan can be considered to have climbed to the highest peak, incomparable. Although it was passed down to his sons, they were in comparison inferior, and then it was passed down to his grandsons, who were more inferior still. Presently it is the sons of Shaohou and Chengfu who have also inherited the transmission. I hope these descendants prove able to continue their ancestors’ achievements, and if they exert themselves that much more, then the Yang family’s reputation can be preserved.

miércoles, 19 de junio de 2013

Wu Chi el movimiento - no movimiento interno del Tai Chi

El Primer Movimiento Invisible del Tai Chi

Martes, 18 junio, 2013 Por Tai Chi en Uruguay

Cada vez que dando clases, me preparo para comenzar una forma de Tai Chi, invariablemente tengo que hacer una pausa para explicar en que consiste el Primer Movimiento del Tai Chi, un movimiento que no siempre se puede ver desde afuera, pero sí siempre se puede “ver” desde adentro y por eso en mi experiencia hay que explicar en que consiste, porque es muy dificil de aprender sin una guía del proceso al que se apunta.

El primer “movimiento” del Tai Chi (o el Chi Kung), es la posición aparentemente estática llamada Wu Chi traducida como “la nada absoluta” o “sin forma”. Es estática solo en apariencia porque todo el “movimiento” se da en forma interna como veremos.

Sin la realización efectiva de este “movimiento interior” no hay Tai Chi ni Chi Kung efectivo y por eso es tan importante tomarse el tiempo en su realización. Dado que no hay movimiento externo real y todo el movimiento- o mejor dicho-, el “movimiento hacia la ausencia de movimiento” se está desarrollando internamente, es que a los occidentales nos cuesta tanto comprender la importancia de quedarse parado durante algunos minutos sin hacer -aparentemente- nada!

La verborragia mental es de tal magnitud que a menos que tomemos conciencia del ruido de fondo de nuestra propia mente y hagamos algo para reducirlo, dificilmente podamos avanzar en la comprensión de las sutilezas a las que nos invita el Tai Chi y el Chi Kung.

Esta postura en si misma es una forma de meditación en movimiento y de donde nace, literalmente hablando, cualquier forma de Tai Chi o Chi Kung. A tal punto que así como sabemos que el roble está encerrado en forma potencial en la semilla, el “despliegue” de la forma de Tai Chi o Chi Kung que luego se haga, está encerrada en este primer movimiento, que como se señaló, es muy dificil de apreciar desde afuera, pero fácilmente de apreciar desde adentro una vez que sistemáticamente nos tomamos el tiempo para realizarlo.

En palabras de Mantak Chia:

“Una de las razones por las que la meditación es un elemento de apoyo muy importante para el Tai Chi es que genera un estado de autoconsciencia que es doble porque nos hace percibir el movimiento de la energía dentro de los meridianos, así como la estructura en la que se mueve dicha energía.La toma de consciencia de nuestra postura empieza desde la primera posición del Tai Chi, llamada Wu Chi. Comenzamos sintiendo las plantas de los pies para ver si todos los puntos de cada una de ellas están en contacto con el suelo. Seguidamente percibimos si una pierna soporta más peso que la otra o si existe alguna tensión leve en la cadera debida a que estamos más inclinados hacia un costado. Observamos si hay tensión en los hombros y si los omóplatos están curvados de tal forma que impidan que el pecho se proyecte hacia adelante. Al llegar a la cabeza, revisamos la posición del mentón y de la base del cráneo, asegurándonos de que el primero se encuentre ligeramente retraído y permita una sensación de abertura de la segunda Por último, alineamos el ángulo de la coronilla hasta sentir un ligero tirón de energía, concentrándonos en una bola de Chi sobre la cúspide de nuestra cabeza. Este tirón indica que toda la estructura se encuentra suspendida entre la fuerza Celestial (arriba) y la fuerza Terrestre (abajo).La alineación estructural es una función natural del cuerpo humano, pero tendemos a perderla después de la infancia. La práctica de Tai Chi nos permite ajustar nuevamente nuestra postura de manera consciente y constante hasta que la alineación estructural adecuada vuelve a fomar parte de nuestro conocimiento corporal natural y dejamos de encorvarnos inconscientemente durante períodos prolongados. Este mejoramiento de la postura física se refleja de inmediato en una mejor estructura mental y emocional. La autoconsciencia que nos hace percibir la postura mal alineada también nos permite ver los estados emocionales negativos que de otra forma no notaríamos.La buena postura es muy importante para la circulación saludable de la energía.”

Tomado del libro La Estructura Interna del Tai Chi, 2005

Autor: Ernesto Velázquez

sábado, 4 de mayo de 2013

viernes, 26 de abril de 2013

Apuntes del libro Chi Gung por L. V. Carnie

Debido a que Chi es energía cósmica universal, se extiende más allá de las limitaciones impuestas por la gente que trata de clasificarla para que se ajuste a ciertas reglas.

El entrenamiento de Chi Kung involucra directamente nuestra mente. Aunque aveces parece física es en realidad una disciplina mental. Debidoa esto las tres características que usted debe cultivar son: VOLUNTAD, PACIENCIA, RESISTENCIA.

Hay que enfocar la mente.

L.V. Carnie

Chi Gung

El entrenamiento de Chi Kung involucra directamente nuestra mente. Aunque aveces parece física es en realidad una disciplina mental. Debidoa esto las tres características que usted debe cultivar son: VOLUNTAD, PACIENCIA, RESISTENCIA.

Hay que enfocar la mente.

L.V. Carnie

Chi Gung

lunes, 22 de abril de 2013

lunes, 4 de marzo de 2013

trio para equilibrar los órganos internos y eliminar dolencias del cuerpo

Cuando la energía vital (CHI) producto del aire que respiramos y alimentos que comemos circula por los meridianos en forma fluida y armoniosa tenemos salud; de lo contrario, empezamos a enfermar.

Estos tres puntos que ya conocen por publicaciones anteriores, forman un trio especial para equilibrar los órganos internos y eliminar muchas dolencias del cuerpo, cuando se trabajan conjuntamente.

1 E36 – DIVINA INDIFERENCIA

2 IG4 – FONDO DEL VALLE O GRAN ELIMINADOR

3 H3 – ASALTO SUPREMO O LA RELAJACIÓN TOTAL

Masajeen en ese orden por espacio de un minuto cada uno, tres veces al día. Esta rutina ayuda a personas que sufren exceso de sudoración, alivia los calores de la menopausia, dolores hepáticos, dolores reumáticos, parálisis facial, fibromialgia, dolores de cuello, hipertensión, migrañas, insomnio, ansiedad, depresión, anorexia, disminuye la agresividad y el fácil enojo.

En mi web www.medicinachinayogaperu.com en el link “Masaje Chino -Tuina” podrán apreciar dos de los puntos, en video

CURSO A DISTANCIA

"Medicina china -técnicas curativas"

4 clases en archivo PDF + 7 libros

Informes: SACZETA@HOTMAIL.COM

Clases y terapias naturales en Lima

Consultorio/ Distrito San miguel telf. 5780228

Maestro César Ramírez T.Ver más

Cuando la energía vital (CHI) producto del aire que respiramos y alimentos que comemos circula por los meridianos en forma fluida y armoniosa tenemos salud; de lo contrario, empezamos a enfermar.

Estos tres puntos que ya conocen por publicaciones anteriores, forman un trio especial para equilibrar los órganos internos y eliminar muchas dolencias del cuerpo, cuando se trabajan conjuntamente.

1 E36 – DIVINA INDIFERENCIA

2 IG4 – FONDO DEL VALLE O GRAN ELIMINADOR

3 H3 – ASALTO SUPREMO O LA RELAJACIÓN TOTAL

Masajeen en ese orden por espacio de un minuto cada uno, tres veces al día. Esta rutina ayuda a personas que sufren exceso de sudoración, alivia los calores de la menopausia, dolores hepáticos, dolores reumáticos, parálisis facial, fibromialgia, dolores de cuello, hipertensión, migrañas, insomnio, ansiedad, depresión, anorexia, disminuye la agresividad y el fácil enojo.

En mi web www.medicinachinayogaperu.com en el link “Masaje Chino -Tuina” podrán apreciar dos de los puntos, en video

CURSO A DISTANCIA

"Medicina china -técnicas curativas"

4 clases en archivo PDF + 7 libros

Informes: SACZETA@HOTMAIL.COM

Clases y terapias naturales en Lima

Consultorio/ Distrito San miguel telf. 5780228

Maestro César Ramírez T.Ver más

Estos tres puntos que ya conocen por publicaciones anteriores, forman un trio especial para equilibrar los órganos internos y eliminar muchas dolencias del cuerpo, cuando se trabajan conjuntamente.

1 E36 – DIVINA INDIFERENCIA

2 IG4 – FONDO DEL VALLE O GRAN ELIMINADOR

3 H3 – ASALTO SUPREMO O LA RELAJACIÓN TOTAL

Masajeen en ese orden por espacio de un minuto cada uno, tres veces al día. Esta rutina ayuda a personas que sufren exceso de sudoración, alivia los calores de la menopausia, dolores hepáticos, dolores reumáticos, parálisis facial, fibromialgia, dolores de cuello, hipertensión, migrañas, insomnio, ansiedad, depresión, anorexia, disminuye la agresividad y el fácil enojo.

En mi web www.medicinachinayogaperu.com en el link “Masaje Chino -Tuina” podrán apreciar dos de los puntos, en video

CURSO A DISTANCIA

"Medicina china -técnicas curativas"

4 clases en archivo PDF + 7 libros